A moment to re-evaluate, discover, and sometimes ask hard questions. Soon after a spring burn ... when the skeleton of the ecosystem is bare ... before it fleshes out and clothes itself again for another growing season ... we walk, look, and think.

Thus, this post will be about (fleetingly in each case):

- increasingly rare plants, benefiting from each other's presence

- helpful burn scars

- a woodhen

- parasites that make positive contributions

- over-populated white-tailed deer

- wilderness trails

- migrant birds return

- plants that like to grow on top of other plants.

Please skip whatever doesn't interest you. Don't worry, be happy.

The morning was deliciously foggy. Out of this pond flushed a Virginia rail and a sedge wren, freshly back from the south. Our stewardship is as much for the animals as the plants. Two rail species breed in Somme's little ponds. Without sufficient habitat, we lose natural species that would otherwise thrive. We have lost many. So we restore. And many come back.

We don't see the rails often. We do hear their calls. Sometimes one flies up as we walk by. We are glad to feel their neighborly presence.

At the edge of the oaks, the rarer wood betony (red-purple) bloomed side by side with the commoner prairie betony (yellow). Both are Pedicularis canadensis.We had been puzzled that a fine prairie plant was somehow called "wood betony." But books from eastern states showed this species in woods - and purplish. Then, as our woodland restoration progressed, we started to see purple ones. It's complicated. (See Endnote 1.)

Burn scars shock some people. Looking raw and wounded. They're from tree-clearing last winter and are a valuable part of the woodland ecosystem. Diversity requires such scars ...

... for some biota. Those are the species that evolved for a specialized niche - created when the fallen trunk of an ancient tree finally passes through the final stage of its fire-dependent life cycle. For many trees in savanna and woodland ecosystems, that stage is not rot. It's fire. As these scars succeed they host impressive waves of algae, mosses, and vascular plants. The endangered Bicknell's geranium is one of many species that we find only or mostly where wood burns

... for some biota. Those are the species that evolved for a specialized niche - created when the fallen trunk of an ancient tree finally passes through the final stage of its fire-dependent life cycle. For many trees in savanna and woodland ecosystems, that stage is not rot. It's fire. As these scars succeed they host impressive waves of algae, mosses, and vascular plants. The endangered Bicknell's geranium is one of many species that we find only or mostly where wood burns out

the competition, for a while

.

Fire is an obviously violent part of nature. But there are more destructive kinds of violence:

Our many big cottonwood trees are shady invaders, not typical of a healthy savanna. Their seedlings can't compete in a competitive turf. Their shade kills some species that would otherwise thrive. Is not death by shade a kind of violence?

Worse in the photo above, the dense shrubs and trees in the background represent a more final brutality. As they wipe out all natural plants and animals beneath, how ruthless should we be in return? We cut, burn, sow, and pamper.

In Somme Prairie Grove's bur oak woodland areas ...

... we have, over the decades, eliminated or thinned buckthorn, ash, hickory, box elder, and more. At least 90% of the woody stems belonged to invaders. Do these photos show a finished state? Far from it. Although, as above, many of the red oaks (shorter-lived than bur or white) have been helping out by falling down dead, other trees grow bigger. The thin-barked hop hornbeam in the foreground (not much a tree of fire ecosystems) was girdled to kill it. Hornbeams make deep shade. To the top left above, you can see other trees so dense they look like a picket fence. They should go. We'll get to them.

But we find that only with shade reduction at the right pace does a thrillingly complex turf develop. More and more

conservative species move around and increase, year after year. But even the much thinned trees above are far too many for this original bur oak woodland.

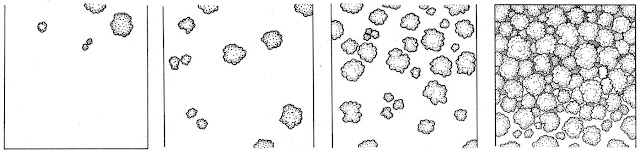

Oak woodland is belatedly recognized as one of our rarest and most threatened ecosystem types. But our science and culture are only slowly coming to terms with what health looks like for it. Paul Nelson's drawings below may help. Not as sunny as a savanna; not as shady as a forest - oak woodland is portrayed in the third panel down:

Looking at the same visual from above:

The "herb layer" of the woodland may be as rich or richer than a prairie:

But Somme's woodlands become increasingly rich and healthy only if shade is removed gradually. When we've cut too much shade at once, we get infestations of such aggressive species as tall goldenrod,

woodland sunflower, and certain briar species. As our measured work proceeds, as

we continue to thin trees and sow conservative seed, we anticipate that diverse good guys will continue to win out.

Plants shown above: In bloom, wood betony, white trillium, and rue anemone. Leaves represent toothwort (which bloomed earlier) and many later-blooming species including golden Alexanders, elm-leaved goldenrod, and many woodland grasses and sedges, difficult to identify now, but here probably including downy rye, awned wood grass, bur-reed sedge, and many others. What additional species will grow here with a bit more light and time? Possibly yellow pimpernel, cream wild pea, woodland milkweed, robin's plantain, and so many others. We don't know. We'll sow them all. They'll decide among themselves.

In the open savanna, three scarlet painted cups are visible. This species is almost gone from the region. We try to help it establish a new population here. The blooming one above is in a deer-exclusion cage. Below it, to the right, is one in a vole exclusion cage. (Later in the year, voles mow down a great percentage of uncaged painted-cups.) A third young plant, uncaged for now, is the purplish, wispy tangle slightly to the left and below the blooming one. How will we divide what time we allot to caging which species this year?

Last year was a painted-cup bonanza, a bit of which is shown below:

Those stakes in the background supported the net that kept the deer out. In this patch we counted 358 plants. Overall we counted 572 plants in 19 separate populations. Too many for us to cage most of them. Is this rare species now doing well enough to hold its own here? At the time, we thought not. Deer and voles consumed many, and as an annual (or biennial), the plant dies at year's end. It will not come back next year, except from seed.

Since we first seeded this species from a nearby population in 2016, every year it has been a thrill to see the first ones emerge, and then more and more, in some years. But we continue to puzzle over its fickle unpredictability. After saving from deer and voles what seed we can, we broadcast it widely ...

Scarlet Painted-cup Numbers at Somme Prairie Grove

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

# of plants | 45 | 1 | 73 | 29 | 162 | 85 | 101 | 572 | | |

... on wettish soil or dry, in full sun or partial shade.

Plants emerge next year in a very few of the seeded areas. Some "sub-pops" thrive in certain small areas year after year, without moving to similar habitat nearby, though seeded there. Other sub-pops thrive in very different areas. In certain spots it shows up for a year or two and then vanishes. Will it return to such areas from time to time, from its seed bank, if one survives? Books and papers don't tell us much. We study it as best we can, in the field.

Native shrub thickets are now uncommon on most sites and

hard to manage. This one is situated in a wet area where most fires, like this year's, burn up to the edge, and then stop. When we pass this thicket during the year's Breeding Bird Census, we regularly see orchard orioles, willow flycatchers, hummingbirds, indigo buntings, and more. They like it.

The shrubs here consist of wild plum (in bloom, above), nannyberry (tall and green now, blooming soon after the plum), two dogwood species and others. These shrubs are occasionally top-killed by especially-hot burns; they then grow back in differing arrangements and proportions. Fun. Without the occasional burning, they'd be replaced by invasive trees.

Seen from another angle, this thicket shows top-killed gray dogwood to the left and monstrous cottonwoods behind, towering over the mature bur oaks, behind them. Those cottonwoods should go. They likely established here on bare soil caused by farming long ago.

Or should the cottonwoods stay for now, in part because removal would be so much work. Certainly, they're scenic.

But in their area they "take up all the oxygen in the room." Nature can't recover under their shade and level of water consumption. Many species of importance to savanna biodiversity conservation suffer from too-small habitats. If controlling those cottonwoods rises to the top of next winter's priority list, they'll go.

Counterintuitively, a main problem for oak savannas and woodlands is too many trees. Decades without fire left the bur oaks below too close together.

We girdled some to kill them. We need to kill more. It's not just the cottonwoods. Tall, skinny trees fighting for the light do not lead to healthy oak woodland. (See Endnote 2.)

But for a different kind of density, here a half-dozen stems of bastard toadflax have helpfully invaded the top of a mound of dropseed grass. The toadflax, wood betony, and scarlet painted-cup are

hemiparasites. All three are conservative plants. Toadflax rarely reproduces by seed; it sends creeping underground stems out to look for victims like this grass. Is that a bad thing? No one understands the complexities and balances of ecosystems, especially nearly-lost ones like the tallgrass savanna. Fine scientists like

Suzanne Simard and

Merlin Sheldrake are helping. We now know that many parasitic animals, plants, fungi, and bacteria play crucial and ultimately healthful roles. In some restored areas, the rare dropseed grass is grossly oversized. The toadflax, betony, and others will bring it into better balance ... and thus open more niches to biodiversity.

When we

began to restore this site in 1980, the patch above was Eurasian pasture grasses and some natural savanna plants that survived heavy grazing. The difficult-to-restore toadflax, luckily, survived thirty feet away on the edge of a wetland. It has since marched up this hill, about one foot per year. Species now seen above also include rattlesnake master and shooting star, from our seed, which will also get credit, later in this growing season, for thick stands of white and purple prairie clover, Leiberg's panic grass, downy phlox, azure aster, and so many others. Fun indeed.

In this Illinois Nature Preserve, visitors are required to stay on the path system unless authorized to step off for stewardship or scientific study. Somme Prairie Grove includes 2.7 miles of maintained trails, if you walk both inner and outer loops. These footpaths are minimal ...

... but they're designed to resist erosion and are reinforced where they pass through wetlands with the wood of cut invasives. In some places, they need more work. How much of our time should we budget for that in 2024? We volunteers decide. More volunteer help is invited.

In the photo below, a path winds through open savanna.

... the oaks are mostly small. Farmers had cut most long ago. Bur oak was the principal tree species here. After the Forest Preserve District bought the land for conservation, few bur oaks seedlings grew back. It turned out that they had needed care. Fire burned them. Deer ate their tender shoots. Most today are re-sprouting "grubs" or oak shrubs, at least 20 of which you can see (top-killed by the recent fire) above. But that dark young tree to the right is a bur oak we had protected long enough that it can now fend off the deer and fire by itself. We had for some years maintained a deer-exclusion fence and raked fuel away before burning. One to a few trees per acre are enough for a savanna. How much time will we invest in protecting more?

In the map below, most trees are invaders. The original bur oaks survived farming in three small areas. Before the significance of natural ecosystems and biodiversity had been recognized, Forest Preserve staff had planted seemingly random tree species including many from other parts of the country and the world. In recent decades we've removed most of these. Bur oaks return, but they're slow.

As I walked past, I peeked in on a woodhen tending her eggs. Eriko had noticed her nest weeks earlier. Woodhens sit tight, even if you come close.

The pussy willow patch below also has a history. For decades it was a minor presence, stems never more than a foot tall, as it was occasionally burned by fire and the re-sprouting stems then eaten by deer.

Willows are a valuable component of the wet savanna community. So a few years ago we found time to put a cage around this one, and we watched it grow to a size that seemed secure. We then repurposed the cage to protect some other deserving plant, but somewhat shockingly, buck deer responded by raking their antlers on it last fall until the bark was gone ...

... killing most stems. Scores of new shoots are now emerging, which the deer will probably eat. Cage it again?

These are the questions, big and small, that we must decide on. We walk and think. Our decisions make the difference.

Acknowledgements

Cook County Forest Preserve staff deserve credit for technical supervision and prescribed burns. We volunteer stewards do most of the rest. Illinois Nature Preserves System staff, Commissioners, and protective laws are important back-up protection, as are Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves.

Thanks to Paul Nelson (and the Tallgrass Restoration Handbook) for the drawings showing the structure of prairie, savanna, woodland ,and forest.

Base preserve map by Carol Freeman. Graphic edits by Linda Masters.

Virginia Rail photo thanks to Tinyfishy on Flickr

Thanks for proofing and edits to Eriko Kojima.

Endnotes

Endnote 1

We started calling Pedicularis canadensis "prairie betony" rather than "wood betony" because we only found it in the prairie. The flowers were always yellow. Pepoon wrote "The prairie form is apparently yellow." We'd never noticed partly red ones until they started showing up in Vestal Grove. When we gather the seeds, of course, we don't know what color the flowers were. So we wracked our minds about where these red ones might have come from. Because our plant populations tend to be impoverished by grazing, shade, and fragmentation, we've always tried to gather seeds from as many and diverse natural populations as possible. We remembered gathering a bit of betony seed from deep in Harms Woods. We checked that area in spring and, sure enough, some of the flowers were red. The red form of this plant has the scientific name Pedicularis canadensis forma praeclara.

Typically, red flowers are adapted to hummingbird pollination. Hummingbirds nest in the woods, not out on the prairie. Could there be a connection here?

|

Today the woods at Somme are rich with yellow betonies, because we seeded them there.

We wonder if the few red ones (which may be adapted to woods?) will increase over time. |

Endnote 2

It's good that most people are at least a bit shocked by tree cutting. This planet generally needs more trees, fewer mowed lawns, and fewer paved surfaces. But for biodiversity conservation, there must be at least some areas where natural conditions survive - or are restored if necessary.

Vestal Grove is the small part of Somme Prairie Grove that still has original bur oaks. All the other big trees on the site are invaders. The Public Land Survey documented the spacing of trees at Somme in 1839. The trees in this area were far apart. As Paul Nelson's drawings suggest, there was in nature every variation of tree density. Today, natural woodlands with widely spaced trees are rare, especially where soils are rich.

At the west end of Vestal Grove stand two trees (below), each with a huge limb reaching west.

These two trees probably stood on the edge of the prairie - here where the 1839 survey showed the trees ending and the prairie stretching west to the horizon.

Original spreading limbs of most woodland trees are now shaded out and dead. But these two huge limbs survived in part because we've cleared many of the shady invaders near them. In the parts of the site where we're protecting young bur oaks, the new saplings may be quite magnificent in a mere two or three hundred years.

Typically on the original landscape, most trees didn't have big lower limbs, as they would have likely been burned off by the fires, especially on the edge of the prairie. These two limbs may have stretched west over grazed pasture starting in the early 1800s, when Euro-American settlers began suppressing fire.

The other natural oak species of Somme Prairie Grove is Hill's oak. In contrast to the thick-barked bur oak, Hill's oak has fire-sensitive bark, is top-killed by even mild burns, and is most often a re-sprouting shrub or "oak grub." (In Somme Woods, to the more fire-protected east, three additional oak species are frequent: swamp white, white, and red oak.)

We have affection and respect for trees. But we cut some, because we love the ecosystem more.

No comments:

Post a Comment