Is this post a hodgepodge of tidbits? Or might it have deeper unity and meaning? I write blog posts rather than books and chapters, in part, because so many key questions are unresolved. Judgements change. Answers, if any, become clear only gradually. In the globally important field of biodiversity conservation, we have both a science and a discipline in their early stages. We keep needing new ideas, flexibility, and change.

This post will range from fen invaders and Thomas Jefferson's bur oak data - to how to burn oak woods and revolutionary class conflict in early Chicago.

The post is kinda long. I divided it into six chapters, for your convenience.

One reader proposed that the unifying principle behind this post may be: “The challenges of biodiversity conservation are great. We may need from time to time to make bold decisions.”

Chapter 1. Times change.

Indeed, they are a changin' in so many ways. Do you recognize the new-to-this-region flower in the photo below?

It's that white spike with a wide lower leaf, an invading orchid, the oval lady's tresses. When first found around here, it was treated as a rare native (Spiranthes ovalis. Swink&Wilhelm 1994: native C=10). Now it's popping up widely and seen as an alien from farther south (Wilhelm&Rericha 2018: non-native - thus no C value). But is it a malignant threat to ecosystems? Not likely.

And do plants moving north with global warming need a different category? “Naturalized?” (For the differences in meaning among alien, adventive, invasive, and naturalized, see Endnote 1.)

No argument about the nativity of this rare plant. The wide leaves and pale flowers above are big-leaf aster (Eurybia macrophylla). This year for the first time at Somme it flowered abundantly and made copious seed. There's a reason for that.

Oak woodlands need help. As part of a long-term experiment, seeds of this aster were gathered from a nearby high-quality oak woods where they sadly now are no more, shaded out, mostly by native invasive trees. The Somme plants, restored by seed, along with other rare diversity slowly increased for decades. But recently, aggressive native woodland sunflower seemed to be suppressing them and everything else. Was this an ailment that could and should be treated? In summer 2022, we scythed the sunflower back in selected areas. We learned a lot. In the photo above, the dark green, pointed, narrow leaves rising above the wide aster leaves are woodland sunflower, re-sprouts after the scything. The big-leaf aster did spectacularly well where we kept the sunflower from shading them out. Our hypothesis was that diversity might keep the sunflowers in balance if we gave some of the other diverse, conservative plants more opportunity to recover a sufficiently competitive turf. A report on this and the larger experiment is in the works.

Similarly with the semi-native quaking aspen: In Shaw Prairie, within Skokie River Nature Preserve, Monica Gajdel (below), another Friend of nature, treats the killer aspen. It's been battled many times here, then let be for years, during which time it has rebounded and largely wiped out precious parts of this preserve. Control takes focus and persistence.

Below, Christos Economou's gloved hands demonstrates the technique:One hand holds a clipper. The other, an herbicide applicator.Aspen, where artificially planted (and sometimes just invading from natural habitat nearby), under conditions today can wipe out entire prairies.

The red indicates herbicide on the tips and sides of live stems:

Notice last year's dead stems, more than twice as big. To control aspen, it's necessary to knock it out a few years in a row. After about three years of intensive control, we've found, it gives up.

Buckthorn is a pushover compared to aspen.

Just as "native" aspen can destroy prairies, "native" sugar maple can destroy oak woodlands. Is this unsettling? It shouldn't be. This post in part is about success and victory after years of learning and struggle.

There is still debate about cutting maples, from time to time. Admittedly, it's a fine tree. So, no doubt, are aspen and buckthorn in their natural habitats. But oak woodlands and savannas are endangered, as are many of their plant and animal species. And maple is an existential threat.

Matt Evans of the Chicago Botanic Garden made the three maps below for the Chicago Wilderness Alliance. They help us understand oak and maple better.

Above, in the six counties of northeastern Illinois, with Cook County outlined in red. Blue dots show where white oak was recorded by Thomas Jefferson's surveyors in the 1830s. (For background see Endnote 3. Public Land Survey.) White oak was the major tree of our region's woodlands.

The map below shows where the surveyors recorded bur oak, the major tree of our savannas.

Most everywhere that didn't have bur or white oak was prairie. Often bur and white oaks were mixed.

Then comes sugar maple, below.

Cook County Forest Preserves are in green. There just wasn't all that much maple forest. Some nice patches border the east side of the DesPlaines River, which protected them from fire. A string of maple in the lowlands border the Palos preserves on the north. An impressive patch in eastern Kane County was no doubt popular with Native Americans who made sugar from the sap. Perhaps they protected it?

Matt writes:

"As of 2022, the frequent fires that have regulated maple species in NE IL have been largely absent for a century and a half leading to a great migration of maple trees into the region, pushing (shading) out oak and tallgrass prairie, and the associated biodiversity. We can see that the PLS surveyors recorded little maple in the region in the 1830’s."

The Botanic Garden, Forest Preserves, the Friends - we protect and treasure natural maple woods. But in oak woodlands and savannas, invasive maple (and its partner-in-crime basswood) needs control. Most effective on maple long term is fire (about which, see much more below). But thinning maples is typically needed too.

The main goal of conservation is to maintain or restore the ancient ecosystems on which most biodiversity depends. In "preserves" generally, keystone bur and white oaks, many of which are old enough that Jefferson's surveyors actually saw them, are not reproducing. Without care, they and the thousands of plant and animal species associated with the oaks are doomed. See ghastly examples in Chapters 5 and 6.)

Chapter 2. Nature Preserves In Trouble

Speaking of Matt, he's president of Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves, a fairly new organization that is wrestling mightily with these challenges. In the photo below, Matt is checking out a tiny prairie in Robinson Park Hill Prairies Nature Preserve in Peoria.

Bit by bit, the prairie shrinks smaller every year, as the surrounding trees, including oaks, kill it. Oak trees can be "invasives" in prairie. But both the prairies here and the oak woods around them are doomed unless they get more fire and other care.

One of the largest, best, and most important original prairies in the state, Revis has annually shrunk such that in 1995 there was more brush than prairie. Then 56% of the prairie was gone. (See Erigenia, Journal of the Illinois Native Plant Society 14: 41–52.) An estimated 75% is gone today.

Above, Philip Juras, gesturing, describes compelling experiences at Revis and introduces Lou Nelms (left), heroic, lonely steward of the preserve for the last decade.

One expert told us cheerfully that, though most of the prairie had been lost, what's left is of very high quality. Is this the best we can do?

Below, Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves director, Amy Doll, makes the case for Revis and for nature preserves generally. They need staff, funding, and especially, local Friends.

Amy (right) enthusiastically introduces new Nature Preserves director, Todd Strole (left). In recent years the Nature Preserve system had lost support. The Director position was left vacant for more than five years. The Friends advocated to re-establish this key role. These two new leaders have very big and difficult jobs.

Soon those assembled at the exhibit were hiking through scrub toward the top of the real thing. Ripe pawpaws littered the ground. They were delicious and energy-replenishing. But cool, shady pawpaw leaves were killing prairie.

At the dramatic top, we had sort of a town meeting and weighed options. $300,000 in contract brush-control work here seems not to have reversed the trend. Prairie didn't recover where the brush was cut. Why not? Could seed gathering and broadcast make the difference? Was the main need more detailed follow-up to kill re-sprouts? More aggressive burning? One DNR person pointed out that the staff were getting older and could only do so much. Some volunteers with youth and energy offered to help. Friends hope to hire regional Field Reps, who could recruit, train, and facilitate a volunteer community that could provide critical help.

Chapter 3. Communities of Nature and Humans

Ecosystems are communities. In parallel, conservation today depends on the human community.

Good doesn't win just because it's right.

Transitioning for a moment from the cosmic to the landscaping in preserve-neighbors' yards, the sign below, on a lawn, made me proud of my Village of Northbrook.

We now have one for our own lawn. The frogs, birds, butterflies, and bees in our yards are interwoven parts of the Nature Preserve ecosystem nearby. Our wild gardens, for example (shown below), are valuable rare-seed-producing ecosystems as they are nectar and food sources. Conversations with neighbors are also an important part of the work. And the sign will help too.

Our seed for rare species (like the formerly Threatened savanna blazing star, below) came originally from tiny, threatened populations - now lost to brush. But the seeds from this garden go back to managed preserves annually, where the refugee blazing star now thrives.

Shown here, on their late summer way to Mexico, seven monarchs industriously pollenate these rare blazing-star beauties. (I can find five monarchs in the photo, if I look hard.) The species of an ecosystem depend on each other. And one of those species is us.

At "field seminars" we stewards study and plan.

We journey here and there to learn more stuff. At the 1580-acre Cap Sauers Holding Nature Preserve we studied a woodland savanna-opening cut from the brush by volunteers in the 1980s. Volunteers are gone from here now, but younger generations are coming along.

We also studied where staff and contractors battled the buckthorn with big machines more recently. We will follow the progress of such areas:

We visited Grant Woods in Lake County.

The restoration work and the public education signage were both impressive.

One treat from Grant Woods was this chair, cut out of a stump.

It seems to tell a story. We wondered what people make of it.

Sitting in it made me feel somehow embraced by ancient nature. People have always been part of the savanna ecosystem and need to be part of it now.

Chapter 4 - Celebrities

I highly recommend two fun and profound books. Andrea Wulf wrote The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt's New World. She also wrote and Lillian Melcher illustrated the even-more-fun "graphic non-fiction" The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt, from which come the pages below:

Humboldt inspired the world. All manner of mountains, an ocean current, and a Chicago park were named after him. Cities around the world held huge celebrations of his birthday attended by hundreds of thousands. He was the first pop-star scientist. He conveyed the fullness of nature in a dramatically new way. His voyage inspired that of Charles Darwin. Humboldt profoundly influenced Henry Thoreau, Goethe, John Muir, Simon Bolivar, and at least two U.S. Presidents.

When he visited Thomas Jefferson, Humboldt admired the man's revolutionary ideas but dissed him on slavery.

Sometimes he was polite about it. Sometimes he blasted Jefferson, the United States, Cuba, and others for their blindness, cowardice, and guilt. Advocacy requires some tact and some boldness.

Humboldt lived much of his life in Paris, then the center of learning and science. Napoleon blocked his mail and harassed him in various ways, sometimes dangerously. Napoleon was jealous that Humboldt was more famous and admired.

Chapter 5 - War and Peace and Scandals

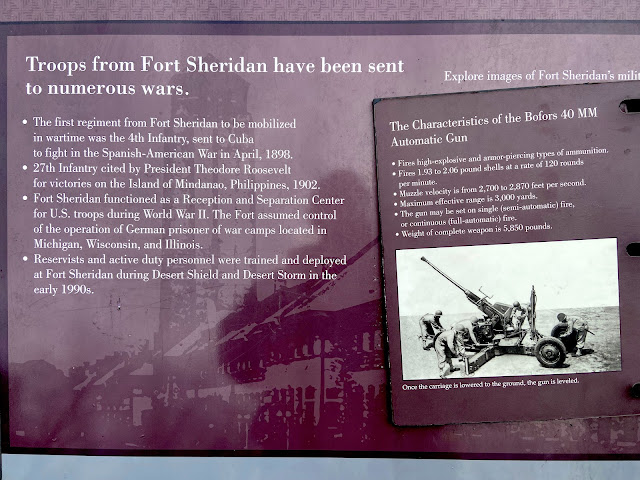

The ravines along Lake Michigan are precious. At least one is a Nature Preserve. The ravine in Fort Sheridan Forest Preserve is not, but it has potential, and some level of public access, which most don't.

We were interested in surviving oak woodland vegetation, which did get a mention on one mud-spattered sign:

And we'll get to that ecosystem soon. But soon there's some history to ponder:This preserve exists now because the land was kept from other uses by the United States Army. And for a remarkable reason. The wealthiest of Chicago fled to Lake Forest in the late 1800s to escape the violence of revolt and revolution.

Someone scribbled "Losers" here. Meaning? To be frank, the bowdlerized language of the sign could use some clarification. The fort was put just south of Lake Forest so that the Army could protect the Robber Barons and other Captains of Industry from The People, who, at that time, were fed up.

Later, the fort was used to train soldiers to fight in Cuba, the Philippines, Middle East, and Europe.

Some people remember wars with nostalgia. Many of us hope fervently that the Russian war crimes against Ukraine will ultimately leave a sour taste for war forever. But history is history.

This is my last and possibly ghastliest war graphic. What can a person say? But now, back to the ecosystem.

Ravines are lovely, dark, and deep. But invasives kill, here as anywhere. Lake County Forest Preserve staff work to restore eco-health. In some places, quality is on the rise. (People scrambling up and down the slopes are another threatening evil. We stayed off the slopes.)

We studied the woodland remnants around the tops. We found many rare species. The champ of the day was wood pea or cream vetchling (Lathyrus ochroleucus). It's one of those rare plant refugees that once were common and deserve to be (and can be) again. Here's what it looks like in bloom:This Endangered plant is a bean, so it could end up contributing improved human nutrition and pest resistance in agriculture. There's fine potential for the return of high-quality woodland health around the edges and crests of the ravine slope. Forest preserve personal recognize this too, as we saw much evidence of stewardship.

But the photo above is ugly in more ways than one. The green leaves barely visible at the bottom are tinged with blue. They are malignant teasel. The blue is herbicide. The leaves were dying. But among them stood towering teasel heads full of seeds. With thousands of seeds falling in all directions, the herbiciding was a waste, a failure, and a missed opportunity.

It's urgent that we in conservation face our scandals. How often should we name scandals site by site. That could raise counterproductive antagonisms. When practical, we Friends try to advocate by praise and asking questions as much as possible.

Many people whisper, but few stand up and loudly say, "We should be ashamed for the state of our nature preserves. People contributed millions of dollars to buy them, on the promise that they would be safe and sound forever."

Fifty years ago, no one anticipated how challenging stewardship would be. But we've now known for decades. At one (unnamed) preserve, white sweet clover was mowed by a restoration contractor after the seed was set, then left on the ground, massively seeding for future years. The contractor was paid for the work. The scandal is in paying. But where does the guilt fall for that? Perhaps on the lack of sufficient staff to follow up? If so, then does the fickle finger of blame point at us, we conservationists who know what's going on but don't speak up and don't advocate and fight for the needed resources?

At another (unnamed) preserve, an unnamed contractor effectively controlled one invasive after parking equipment nightly in a patch of a worse invasive and then (through seeds and mud on tires) spread that evil over hundreds of acres. Neither the contract language nor staff supervision stood in the way. The contractor was paid. There were no repercussions.

Chapter 6. Generations and Legacies

What inspires me most in recent years are the initiatives taken by (often youthful) volunteer leaders with Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves.

What inspires them (and me, for that matter)? As I write today, I repeatedly hear loud flocks of cranes flying over. Rushing outside this time, I see fifty cranes forming a "kettle" or vortex above where I know stewards are today burning a bonfire. Updrafts lift flocks of cranes high into the heavens. These ancient birds are so smart. They largely glide from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, making crafty use of whatever thermal vortices they find. When they take advantage of our bonfires, I all-the-more know that we and they are all in this together.

Cranes have one of the longest fossil records of any bird - going back millions of years. They survived multiple glaciations, only to go extinct as breeding birds east of the Mississippi when Euro-Americans took over. Later, conservation reared its thoughtful head, and now cranes breed exuberantly in many forest preserves where restoration welcomes them, and hundreds of thousands fly over every spring and fall. We're in a flyway. It's a seasonal privilege that stokes our hopes.

Lisa Musgrave snapped this spectacular photo as mama and papa cranes shepherded their babies across a Forest Preserve bike trail at Deer Grove East. Cranes showed up and started breeding here the first year after major restoration started. They've successfully raised many "colts" there.

Being a medic for injured nature has a lot in common with being parent to babies. Wisdom and finesse often succeed where force doesn't.

The folks below are such parents of nature, taking a break.

As flocks of cranes fly over, halfway through a volunteer "workday" - these stewards are snacking, joking, and thinking aloud, sprawled in a firebreak mowed by staff. Staff and volunteers do different kinds of work, which reinforce each other.

The yellow flags here represent individual dogwood shrubs that had badly damaged parts of the very high-quality Somme Prairie. As with the aspen at Shaw Prairie, nothing else had worked, so the volunteers are annually cutting and herbiciding annually. Now just a few nasty stems are left. The public payroll probably can't fund this level of detail. We need both staff and volunteers.

How much pampering makes sense in biodiversity conservation?

Above, fringed gentian and eared false-foxglove are caged for protection from deer and voles. The seeds (that mature here in quantity only when so protected) are spread widely when ripe into receptive habitats. If dedicated people do this for a few years, perhaps these nearly lost species will build up large enough numbers to be able to make it on their own.

As we edge up toward the climax of this long post, we'll consider Pilcher Park (just two photos) and controlled burns (three more). Nature

Preserve staff, in fall, with vegetation dormant. The first photo, by Mike MacDonald from chicagonaturenow.com, celebrates the richness of spring flora in a wetland seep here.

This 293 acre Nature Preserve "is one of northeastern Illinois’ premiere woodlands with outstanding spring wildflower displays and old-growth trees."

It needs serious help. Donated to the Joliet Park District in 1921 by Robert Pilcher, it's been putatively "protected" ever since. But has not had prescribed burns, which we now know it needs. The ephemeral spring flora survives. But on October 31 when we visited, there were no inspiring photos to take. The ground was mostly bare. In the dark of the now over-dense canopy, there had been no summer or fall flora, which represent most of the plant species, and on which most animals depend. There was no reproduction of the magnificent old bur and white oaks. Expandable, recoverable patches are said to survive.

We did find one hopeful sign, the bottom of which is shown here:

We guessed that this sign was installed when the site was officially granted Nature Preserve status in 2012. The park website shows that

they do sponsor at least some restoration - though apparently not focused on its most needy, highest quality areas. The friendly and professional staff knew a great deal about the park's facilities for weddings and such, yoga, kids programs, and the greenhouse conservatory. But they could tell us nothing about volunteerism or restoration.

The soon-to-be-hired Friends Field Reps should be able to help. What's needed? Recruitment, training, mentoring, and facilitation. You might think that kind of work is technically easy, but it's not.

Field Reps need people skills and the ability to facilitate state of the art applied science. Consider the photo below, which shows a burn that was not as good as it could have been. Such burns are common, though nobody's fault, really. Perhaps some day there will be enough resources and public knowledge that a poor burn will be a proper scandal. Biodiversity declines because of them. And yet a poor or mediocre burn is all that most sites are likely to get.Little flames won't do much good. They will do some.

There had been hot, dry, windy days earlier in October when a burn could have done a lot more of the work biodiversity conservationists hope for. Also, for public heath, the fire would have been hotter and the smoke would have risen and dispersed high in the sky unlike today, when it hugged the ground.

Then also, it was shut down too early. This complaint reminds me of the joke about the diner who complained, "The food here is terrible! And the portions are too small!" But, as is often the case, the best burn conditions came later in the day, when temperatures rose and humidity fell. Today, the contractor shut down the burn early so workers could spend their time spraying water on smoking logs. They did it until after dark. But burning up downed logs is part of the work that a natural oak woods fire is supposed to do. It's good. If you put out smoking logs, then you'll have to do it again after the next burn, and the next, and on. For better or worse, that work often fails. Consider the log below, which had a lot of water sprayed on it soon after I took this photo. It had seemed out, but deep inside it wasn't.

Burning log at unnamed site. November 22. 4:34 PM

Same log. November 23. 8:23 AM

Same log. November 25. 2:07 PM

Secret peek into the end of that log. Also at 2:07.

The logs often burn for days. That's good. It's nature. Preserve visitors may make concerned phone calls. They need education and, in my experience, they typically appreciate it.

Well-intentioned and good staff make the rules and the decisions. They listen to the public, as they need to do. We, the public, are part of the problem and part of the solution.

Staff and volunteers need to collaborate - with vision, commitment, openness, and generosity of spirit.

In the photo above, Friends director Amy Doll (second from the right) poses with six candidates for one or two Friends Field Rep jobs. They all seem to have commitment, vision, openness, and generosity of spirit. Important parts of the future are soon to be in their hands of the one (or two, if the funding comes) that get(s) hired.

If you feel a generosity of spirit, it would be great if you could donate to Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves.

Web address:

Friends of Illinois Nature PreservesU.S. Mail address: Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves, 224 Concord Drive, DeKalb, Illinois 60115

Endnotes

Endnote 1

The words alien, adventive, and naturalized - along with non-native and weed may mean slightly or very different things, depending on who uses them.

An adventive plant is one, according to various dictionaries:

- Not native, but introduced by humans to a place and has since become naturalized.

- Not native and usu. not yet well established, exotic.

- Not native and not fully established; locally or temporarily naturalized.

Often it's helpful to consider the history of a word. So I checked the Oxford English Dictionary. It gave two definitions for adventive:

A. "of the nature of an addition from without"

B. "an immigrant, a sojourner"

Perhaps not so helpful in this case. Frankly, those people speak a different language over there, especially as regards nature; they have nothing surviving remotely like our natural areas. So we struggle to theorize, invent, define, conceive a land ethic, and otherwise figure this stuff out pretty much from scratch.

The word naturalized is easier.

Although this word has many other uses, in ecology it just means a plant from elsewhere that has become part of nature in some new place.

Endnote 2

The jury is still out on the value of importing pests to combat other pests that seem worse. In this context, it seems worthwhile to tell the story of purple loosestrife beetles and the heroic contributions of Donna Hriljac, John Schwegman, and Sidney Yates.

European purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) had destroyed millions of acres of valuable marshes and swamps in eastern North America. Billions of animals and plants died, some becoming endangered in the process. Illinois state botanist John Schwegman saw that plague invading Illinois and conspired (legally) with other leading midwest conservation leaders to request the U.S. Department of Agriculture to find European pests to combat it.

Year after year, they appealed. They got nowhere. Then Donna Hriljac heard of it through her work as a spirited volunteer with the North Branch Prairie Project. Donna was also a Sierra Club activist and the principal volunteer coordinator for the re-election campaign of Congressman Sid Yates, chair of the House committee that appropriated the funds for the Department of Agriculture. She asked him to fund it, and he did, the next day.

We need the scientists and the state conservation institutions. But we also need community.

Researchers found beetles that would eat nothing else but purple loosestrife. Here, they turned out to be a good but imperfect solution. Companies reared and released vast numbers of such beetles. As part of the same program, high school students did the same. At differing sites, for unknown reasons (it's often insanely expensive to study such stuff) the beetles either wiped out the loosestrife or did little. Kishwaukee Fen was one of the sites where the beetles failed. But bless them at other sites where they worked ecological miracles.

Endnote 3

The maps in the main text show where Thomas Jefferson's "Public Land Survey" found bur and white oaks (and some sugar maples) in the Chicago region. If you didn't know, in 1785 Jefferson launched a survey of new land (captured from Britain in the revolutionary war and bought from France) so that the government could sell it to farmers without disputes over metes and bounds. The government needed money to build roads, pay promised back wages to the soldiers who won that war, and send an ambassador to France. (Ambasador James Monroe bought the Louisiana Purchase for 4 cents an acre, not a bad deal.)

Jefferson's surveyors reached here in 1839, taking data on land increasingly inhabited by Euro-Americans but long molded by Native Americans. To securely mark section corners, the surveyors carved ID numbers on the three nearest trees and recorded the distance from the corner along with the girth and species of each tree. Unintentionally, that became our best and most detailed record of the ancient ecosystem, with data at every mile in the state, north to south, east to west.

References

Robertson, K. R., M. W. Schwartz, J. W. Olson, B. K. Dunphy, and H. David Clarke. 1995. A Synopsis of hill prairies in Illinois: 50 years of change. Pp. 9–20 in T. E. Rice, editor, Proceedings of the Fourth Central Illinois Prairie Conference. Prairie remnants: Rekindling our natural heritage. Millikin University, Decatur, September 17–18, 1994. Grand Prairie Friends of Illinois, Urbana

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Eriko Kojima and Christos Economou for helpful edits and proofing.

To me the concepts that a plant species’ range is fixed and that its presence beyond that range is “bad.” are erroneous. Ranges are determined solely by the existence of herbarium specimens and the knowledge of those specimen’s existence by the botanist who is determining a range.

ReplyDeleteThe journey of a specimen to a herbarium is a long one, one that is not often made I believe. How often have you observed something “interesting” but chosen not to collect it and send it to a herbarium?

Spiranthes ovalis is particularly “interesting.” In 1896 a specimen of Spiranthes cernua was collected in New York state. It was subsequently determined to be Spiranthes ovalis var. ovalis, and finally to be Spiranthes ovalis var. erostellata. That puts it in New York about 120 years before the first record species for the state and north of its acknowledged range.

In McHenry County, Illinois, I have stumbled across specimens while crawling along an animal trail herbiciding tall, black locust saplings. To the best of my knowledge a specimen from this location has not been added to any herbarium collection.

This Spiranthes is often only 4 or 5 inches tall, easily hidden by taller vegetation, and, I am convinced, often missed by people. It blooms for a short time. I believe that it has been here a lot longer than recent finds suggest. That strong southerly winds have been suddenly blowing minuscule, embryonic seeds into “northern” Illinois seems a bit of a stretch. Even if this hypothesis is true (I doubt that people are planting it everywhere), then its range is being naturally expanded and this should not be disturbed by us.

You are one of the most detail orientated people I’ve met. I will never equal your on-the-spot botanical knowledge. I will also never, nor have a desire to, have your masterful way of dealing with people. However, conservation needs other talents beside these admirable qualities. When you write “There’s not enough time for supervision or quality control.” I am really turned off.

ReplyDeleteWhen I first started volunteering, I helped cut gray dogwood at a prairie restoration. I came back to the location the following year to see the result of my effort. The gray dogwood had all sprouted to about waist high just like is shown in your photo of the cut and treated aspen. When I saw this, my thought was that the time I had given as a volunteer was wasted.

You wrote, “After about three years it (aspen) gives up.” I was not resigned to accept this arduous work for small results. Instead, I tried other methods mentioned on the herbicide label. I found that by not cutting clonal woody species, but rather making cuts around the stem (frilling) and then applying herbicide, that control can be achieved after the first treatment using a lower concentration of herbicide. If knowledgeable people had done their homework, then much more could have been accomplished for the same amount of effort earlier.

Another example is applying basal bark herbicide. People applying this herbicide have caused significant damage to high quality natural areas. I kept records of the number of days until precipitation occurred after I had done applications. From these basic records, I showed the damage to adjacent vegetation could be prevented if people simply did not apply this herbicide when rain was forecasted within the next several days. Also necessary is following the directions on the label to not let the herbicide run down to the ground. Not applying herbicide before rain is forecast is a very simple factor that has an enormous impact on the quality of the results.

The list you give for mistakes done by contractors is only the tip of the iceberg. However, to be fair to hard working contractors. The staff, the stewards, and I have all made mistakes. I must risk failure on a small scale to improve my practices. The contractors will do whatever they are asked if they are paid for it. More intelligence needs to be built into the contracts that are put out for bid. We need more research to make stewardship more effective for the time that is expend. We also need quality control. Without it, how do people know if all the time and money that is put into conservation is a good value or even worse causing more damage than improvement?

I know the people who do quality control are very different from most conservationists. They need lots of mathematics and have industry backgrounds. However, people who can do both quality and have conservation knowledge are what is needed. The billionaires who control most of the money did not get that way by not expecting results. If they are going to invest their money into conservation, then it needs to be proven to them that the money is being used effectively.

I also realize no one likes criticism. However, we all need to realize that when an ecologist tells us we made a mistake it is so we can achieve our goal and do better. We can all do better.

James, I very much agree. The staff owe it to the public, whose taxes fund the preserves, to put the needed time into supervision and quality control. I suspect that many, like me, do their best to balance the urgent "get stuff done" needs with spending time on difficult details.

DeleteYes, failures are unavoidable. Yes, small failures are part of experimental learning, and yes, large failures could be avoided by synthesizing what people (yourself included) have learned and by adopting standards. Society for Ecological Restoration, the Chicago Wilderness Alliance, and others have taken steps in that direction, but our "immature discipline and science" is far from where we need it to be.

As for clonal shrubs, the Somme Team too has tried various forms of this. Some results have been better than others, but no approach, for us, has done the job completely with one application. As you point out, differences between days (seasons and weather) and sites (soils, age of shrub clump, etc.) may be important.

Yes, we all have strengths and weaknesses, and all our varied abilities and levels of dedication are needed. I admire your efforts toward good communication, above.

The differences in herbicide effectiveness I observed were between Nachusa Grasslands and western Cook County. The colder temperatures and drier conditions in sandy soil at Nachusa Grasslands will occasionally cause a small percentage (1-4 %) of Asian bush honeysuckle to die without intervention. This was presented by Ms. Leah Kleiman.

Deletehttps://www.nachusagrasslands.org/uploads/5/8/4/6/58466593/kleiman_poster.pdf

I did not believe Asian bush honeysuckle would die without intervention as presented in the previously mentioned results. I had to go to Nachusa Grasslands to verify this myself. I have never seen an Asian bush honeysuckle die from environmental stress in western Cook County.

When I applied herbicide at Nachusa Grasslands, I was controlling shrubs with half the amount of herbicide I am now finding is needed for equivalent control in western Cook County.

Somme Prairie Grove is not that far away with soils that are not that very different from my location. My experiences should apply to your site.

I have been applying glyphosate to cuts in stems of gray dogwood and staghorn sumac for a few years and buckthorn for even longer. I believe I can control any of these species at Somme Prairie Grove with a 95 percent, or greater, control of treated stems with 25 percent active ingredient glyphosate using this method compared to all stems resprouting when 41 percent active ingredient glyphosate is puddled on each cut stem.

The 95 percent number is my goal. However currently I’ve been getting near 100 percent control with this technique. The one stem that was not killed must have missed getting herbicide applied. I know with more trials I can drop the percent active ingredient herbicide I am using further.

If the Forest Preserve District of Cook County would allow a trial, I would be willing to walk you through the technique I am using. It is not very high tech. I just use a chisel to make cuts. Kids could use a vegetable peeler to do the same thing on small stems. I then come back later and drip herbicide into the cuts from a paint brush I keep in a metal can.

If the technique does not work then you are free to call me a charlatan.

To be specific, when I wrote above “…compared to all stems resprouting when 41 percent active ingredient glyphosate is puddled on each cut stem.” I was referring to the root sprouting species I’ve trialed, namely gray dogwood and staghorn sumac. This concentration and amount of glyphosate applied to buckthorn stumps should give good control. Applying herbicide to cuts around stems (frills) on buckthorn will give near 100 percent control. The advantage of applying herbicide to cuts around stems (frills) on buckthorn is that excellent levels of control can be achieve with a lower concentration of herbicide than is required for cut stump application. There are also other benefits I mentioned in the treatise I wrote.

Deletehttps://grasslandrestorationnetwork.org/2018/02/18/cut-stem-treatment-on-buckthorn/

Another factor that can be important is time between an herbicide application and a prescribed fire. The longer the time between when a basal bark herbicide application occurred, from fall to late winter, and a spring prescribed fire, the better the control that I observed. After all my other applications, when a prescribed fire did not occur the following spring, the percentage control was roughly the same. Therefore, basal bark applications should occur in areas where prescribed fire is not planned during the following spring.

DeleteI have not tested it, but I expect if glyphosate was applied to cuts around stems and then the shrub was burned down to the ground in a prescribed fire this would likewise reduce effectiveness. The prescribed fire would remove the top, just as occurs with cut stem application. As experience has shown, cut stem application has proven to only reduce stem size of root sprouting species after the first application.

Kirk Garanflo asked for my herbicide calculations and brought the following to my attention. I did not factor in changes in density when calculating the volume of concentrate to dilute to a final volume.

DeleteI redid the calculation factoring in density. The percent active ingredient of the dilution I mentioned above is 26.3 percent, instead of 25 percent.

My goal when applying herbicide is to get the volume applied to within +/- 25 percent of my target amount for each individual invasive species of a given size. Some individuals require more herbicide, and some require less due to numerous uncontrollable factors. The measuring cups provided with the Roundup containers also have more error than would occur if I used graduated cylinders or a precision scale.

Considering the above, I do not think the differences in percent active ingredient I am applying versus what I previously wrote would make much of difference. However, I am making the correction here to be as accurate as possible.

Looking through my notes, I think the above-mentioned failure of the herbicide application to control staghorn sumac was because of when the herbicide was applied. Applying 26 percent a.i. glyphosate to frills around sumac had 100 percent success on November 21st. This same type of application on December 11th had a high rate of control but some sprouting. In contrast, when I did this same type of application on February 12th, the application was a complete failure. I was only able to do this type of application on February 12th because it was warmer than average, so the stems were not frozen. However, the ground was frozen. It must have been the season and frozen ground that prevented the herbicide from being transported to the roots. Note for the future, do not apply glyphosate to sumac in winter.

DeleteWe need thoughtful, deep thinkers. We also need doers; movers and shakers. Steve fits that bill more than most.

ReplyDeleteThe natural world is infinitely complex and mistakes will no doubt be made by some in our community. But - inaction is certainly the ‘worst’ of mistakes

Is collecting basic data so onerous? When I apply herbicide, I count the number of the invasive species I have treated. This helps me know how effectively my time is being spent and plan for future work. I also come back later to see if other plants have been impacted and mark them with surveyor’s tape. The next year, I then survey to see what percentage of the invasive species were effectively controlled by the herbicide application and if impacted native plants recovered or die. Applying herbicide is a balancing act. One that requires incremental shifts to get success while minimizing damage.

DeleteIs it onerous? Oh my, yes! For any scientifically valid proof, an experiment must be repeatable and the results must be repeatable. In herbiciding, for example, combinations of herbicide type, herbicide concentrations, differing techniques, and time of application (spring or fall) combine to make large numbers of samples necessary. Keeping accurate track of these over what may become several years of study can be very difficult in the wild.

DeleteOnce having proved (or disproved) some hypothesis there comes the tasks of writing a paper with sufficient depth and quality and of getting it published. Both of these things are needed if all of the work expended is to be of actual use to large numbers of people. Think back to high school where writing an essay and then reading it aloud before a class were probably detested almost as much as taking a test - any test! Those two dislikes I fear are carried on well past schooldays.

All of these factors may explain why collecting data is not done as much as could be desired. Kudos to all of those who have the fortitude to do so; unfortunately, they are few in numbers.

Kirk, well put. On the other hand, I've long thought that "scientific papers" are not the best way to study and publicize best restoration practices. We need better ways for large numbers of busy people to share and learn from what works and doesn't, day to day.

Delete@Steve: there is a NE IL Stewards facebook group that has hosted discussions but I'm not sure how active it is. The biennial Wild Things Conference might also be a good venue. Your blogs have always been informative to me too. - Kathy G

Delete@anonymous - Correct - the worst action is inaction. We are all culpable in nature's demise if we throw up our hands and say 'It's impossible!' Look at what's already been accomplished - were there volunteer-stewarded sites 60 years ago? 50? We have to credit Steve Packard and many others for the creation of a culture of conservation, for the development of trust and mutual accountability in these partnerships with the Cook County Forest Preserves system and other agencies for where we are now. We cannot rest on our laurels, nor allow ourselves to be buried in meetings about it, nor just give up. The preserves - and our great-grandchildren who will hopefully learn to love them as we do now - need and deserve our continued care. - Kathy G.

DeleteKeep making observations and using applied science! Great photos can really help illustrate your message - keep it up!

ReplyDeleteThere is no shortage of invasive species so the repeatable part is not a problem.

ReplyDeleteSeveral years of study is not a problem. Herbicide effectiveness is usually measured one year after application. I’ve been applying herbicide for ecological restoration purposes for 15 years. Compared to many of you I am just a newbie.

Writing papers is not a problem either. There are plenty of people who would be willing to do this for money and recognition. Especially, if they were handed an unrefutable amount of data collected by many different stewards which they did not have to collect it themselves.

Making the work useful to “a large number of people” can be a problem. My experience has been that the amount of herbicide needed can vary widely depending on location. Therefore, it is imperative that data is gathered at each site to track results so adjustments can be made specific to the site.

Unlike most stewardship work, collecting data is not physically taxing. Therefore, much of this can be done before or after someone has become spent from doing other tasks.

I see you have done some editing. The quote from your above blog post now reads, “But the basic problem is not laziness or incompetence or indifference. It’s that the challenge is too big for the resources. There’s not enough capacity for needed supervision and quality control.”

ReplyDeleteI grew up before the development of Roundup ready soybeans. During the summer, high school students including me used to walk the fields, pulling weeds, for a little spending money. Now interns don’t want to pull weeds. They just want to spray. They insist on spraying even though the herbicide will kill any species in the targeted group of plants near the invasive species. If what I’ve been told is true, then not wanting to work hard is a problem.

I already hit upon the problems with competency.

I must call B.S. on there “… not being enough capacity for needed supervision and quality control.” If the Masters of the Universe in Lake County insist that Standard Operating Procedures, Vegetation Management Guidelines, or whatever you want to call them must be developed then they would be written. I also don’t believe there is enough money to pay people to do invasive species control but then not enough money to have the results evaluated. This might have been true in Cook County. However, with the taxpayers doubling the Forest Preserve of Cook County’s budget, the capacity for supervision and quality control should not be a problem going forward. Maybe I’m wrong. If so, show me the numbers.

However, I do believe there would not be nearly enough capacity for a donation run nonprofit organization to be a watchdog on all the work that is happening in the preserves.

Ecological restoration needs people with the ability to do detailed work comparable to a museum conservator restoring a famous painting. Instead, we get demolition crews burning a few hundred gallons of diesel in tree eating machines who then broadcast spray a site. What ecological restoration has become is shameful.

James, yes, I edit. My blog posts change as I get new information and in response to comments. I find that people continue to read them years after they're first published, so if I think I can improve them and can find the time, I try.

DeleteI also have sympathy on your "calling B.S." on my summary statement about "not enough capacity." The failures are not acceptable. I agree. But let me give an example that is both outrageous and understandable at the same time.

I recommended to one agency that they pay attention to a rare remnant shrub savanna opening in an oak woods. In a report, I summarized the value of its many rare shrub species, the young oaks that seemed like a natural part of its dynamic, the sedge diversity, and the many rare and endangered herb species that associated with the shrubs and oaks.

The agency staff did nothing for a couple of years, and then they sent in a crew that cut all the shrubs and oaks. I frankly reported on what seemed to me like a mistake (although not a fatal one, as at least a few of the same shrubs and oaks survived around the edges). I also pointed out that the area was thick with re-sprouts and that the buckthorn re-sprouts would probably grow faster than the ninebark, New Jersey tea, viburnums and other desirable ones.

Thus the next step in this tragedy of errors was for them to send in folks to foliar spray the buckthorn re-sprouts, unfortunately during the growing season and without needed guidance. They sprayed the native shrub re-sprouts too, apparently eliminated New Jersey tea permanently from that preserve, and killed off one Threatened herb species.

I know a few of the people involved. I like them. They're competent and dedicated. They're also frustrated. Failures of communication within the system seem to be beyond ready control. I had offered to do the work myself, for free, but the offer was turned down, for understandable reasons too long to outline here.

Individual agency staff people and individual volunteers are often not able to accomplish what's needed. Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves are hard at work to build communities of stewards what will have the abilities and dedications and capacity needed to pay closer attention to sites like this. I've seen that approach solve such challenges again and again.

That's only one solution, and professional solutions are clearly needed as well.

What would be done to me if I went and dug up plants in the county’s preserves? Much less plants on the threatened and endangered species list. They would put me in jail, haul me into court, and give me a big fine.

DeleteWhat you wrote above similarly happened to a preserve near my house. On his death bed, a long-time local volunteer donated money to have invasive species removed from a natural area. An outfit came and foliar sprayed invasive shrubs, and native shrubs too, during early summer. I went and took photos of the damage to patches of bloodroot, Trilliums, Triosteum, chokeberry, and other things. I sent them to the director of conservation and his boss. The director of conservation told me he would keep an eye on these contractors in the future. The contractors were told not to spray until late October or early November. The next year, they foliar sprayed buckthorn in early summer again. Where patches of spring ephemerals had been impacted from spray drift creeping Charlie filled in the bare ground. The buckthorn they had foliar sprayed were not even killed. As far as I know, nothing was done about this and the people who did this were still paid.

What is needed is Standard Operating Procedures just as occurs in medicine. The first step of the Standard Operating Procedure should be to have a botanist/ecologist survey a site before work occurs. Any native plants that might accidentally get treated with herbicide (Viburnum, New Jersey Tea, etc.) should be marked so they are highly visible. I use surveyor’s tape. This way an applicator should have no excuse for applying herbicide to a marked non-target species. Just like before a prescribed burn occurs, a map should be created. This map needs to show rare species, high-quality areas, etc. The method of herbicide application, time of year, and other factors should be spelled out in the contract. Penalties for damage should also be spelled out in the contract.

The bastards who are doing growing season foliar spraying of uncut shrubs/trees in our natural areas need to be stopped.

This is a tricky one to unentangle, but creating and nurturing a culture of conservation, such as many stewards are doing - or attempting to do - is essential. And I feel that some of the agencies are working really hard and diligently to accomplish miracles, considering the overall level of public and political apathy to their work. Other agencies may have just given up and said "we will do what we can within what's possible within our dwindling annual budgets." Or... stepped away from land stewardship altogether, which is tremendously sad to contemplate. Volunteers who ask hard questions might be seen as annoyances, or worse, as liabilities. What I wonder is, are there any regional discussions happening around these issues, where the many bright minds who care about the future of our rare flora, and have a role in their survival, might brainstorm practical and long-range solutions? I also am curious about looking at ecosystem health as parallel to public health evaluation - what percentage of invasive species cover is considered acceptable? Is it zero? Or some other number? There are a lot of agencies working sometimes solo, sometimes collaboratively, but stuff like phragmites and teasel don't care about property boundaries - are region-wide collaborations practical to both educate and address those? The two agencies I work under have been wonderful in equipping me with the tools and support needed for stewardship. There is always more to do, but if we don't continue to build and nurture that culture of appreciation for our nature preserves, I fear that future generations to whom these preserves are entrusted will not know what to do with them. And I want to just say a word in support for the Forest Preserves of Cook County, the Lake County Forest Preserves, and the Volunteer Stewardship Network of the Nature Conservancy of Illinois - they do a LOT of youth education. I would like to see more of this in the public schools and certainly in our faith-based organizations. How can we deepen those already-existing connections? - Kathy Garness

ReplyDelete