And yet another species is revived on Langham Island.

Bit by bit, an island Nature Preserve is coming back from a near death experience. Until recently, we were still hoping and watching for the re-appearance two rare clovers, a rare violet, and a rare grass. Now, though not how we expected, that rare grass is back, baby.

(For “Why Care About A Rare Grass?” – see Endnote 1.)

The official Nature Preserve plan of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources puts it this way:

Langham Island – The preserve includes populations of two Illinois endangered species, the Kankakee mallow (Illiamna remota) and corn salad (Valerianella umbilicata) and has historically supported the state endangered two-flowered melic grass (Melica mutica), buffalo clover (Trifolium reflexum), and the federally endangered leafy prairie clover (Dalea foliosa).

Thanks to brush cutting and fire, the mallow and the strangely named "corn salad" now bloom on the island by the hundreds. Then, on June 9, 2022, Langham volunteer John Sullivan found an unusual-looking grass, consulted the iNaturalist app, and learned it was a melic grass – was it the Endangered one?

Independently, Langham and Somme volunteer Christos Economou had launched a search for rare grasses that might have been important to our savannas at Somme, Shaw, and elsewhere – for example, the melic grasses. To help him out, his friend Katie Kucera checked iNaturalist, to see if any populations had been found recently. Yes, she said, one population in Cranberry Slough Nature Preserve, let's go there and see if we can find it. And later she reported, oops, last Thursday, a melic grass was also reported from Langham Island, found by our friend John Sullivan!

“Woah!!” reads Christos’ text reply. Grass discoveries can get pretty emotional.

Katie replies: “Wow! I was there but didn’t know.” She had been on the island, cutting brush with John and others, but he hadn't mentioned it.

iNaturalist identified the plant tentatively as Melica nitens, tall melic grass, not Melica mutica, two-flowered melic grass, the Endangered one. But they're similar. How certain was the ID? Could another endangered rarity now be back? But there will be twists as this story unfolds.

In the 1800s, physically handicapped but intrepid botanist E. J. Hill first documented most of the rare plants of Langham. According to H.S.Pepoon’s flora of the Chicago region, Hill also reported finding the (now Endangered) two-flowered melic grass near Chicago:

Base of limestone ledge near Lemont. A single plant. (Hill 1899). Others may be found if careful search is made, or the species may be extinct here.

Or – there’s a third possibility, as suggested by Pepoon in a comment he added under tall melic grass:

Reported from Lemont by Prof. Hill. The chances are that the Lemont plants of Hill are all of this species as it is the common Illinois species.”

Hill was a great botanist. But the equally great H.S.Pepoon suspected he messed up on his identification of this one.

And also, yes, maybe tall melic grass was common then. Today tall melic grass is one of our rightly-celebrated, rare “refugee species” that may be making a comeback in areas being restored by fire.

Mohlenbrock’s 1972 Illustrated Flora of Illinois affirmed the presence of two-flowered melic grass in four northeastern counties including Cook and Kankakee. He added that “It is one of the most attractive grasses in the state,” but “is becoming rare or even extinct in the northernmost counties. Glassman (1964) reports no collection of it from the Chicago region since 1899.”

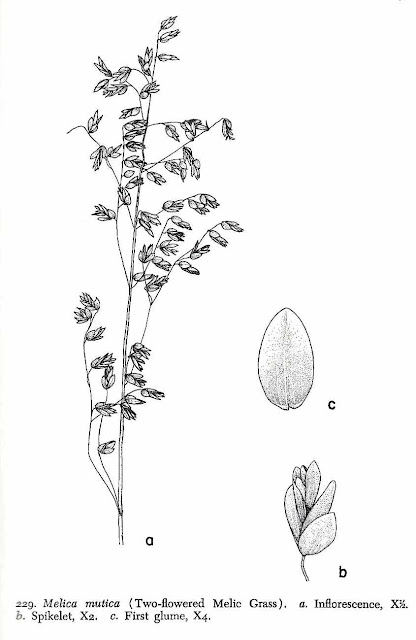

Mohlenbrock drawing of Melica mutica

Does its beauty captivate you?

Spoiler: Mohlembrock's is a highly respected book. But what it reported for Melica mutica in this region was wrong.

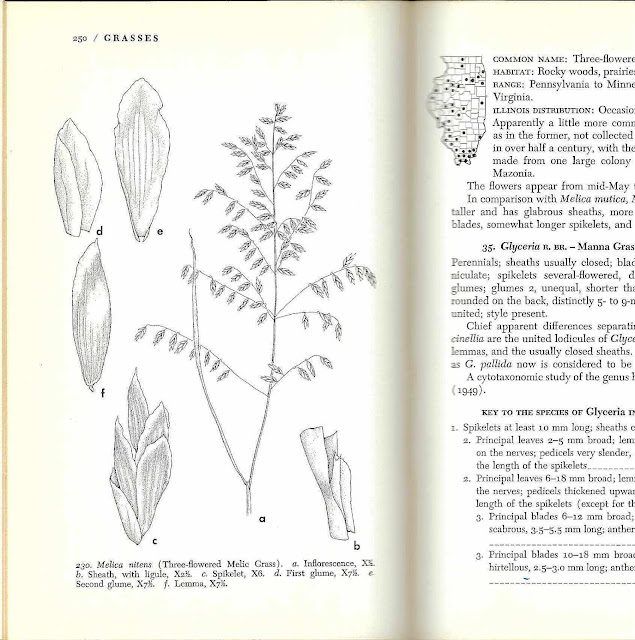

About Melica nitens, Mohlenbrock offered a second gloomy report: “Apparently a little more common than M. mutica, but, as in the former, not collected from the Chicago region in over half a century, with the exception of a collection made from one large colony in Grundy County.” In other words, they were both by then rare plants.

We understand that the Melica Nitens Appreciation Society is preparing a campaign to advocate for recognition of equal beauty for this other, fine, rare grass.

Swink & Wilhelm in Plants of the Chicago Region (1994) cover two-flowered melic grass without giving Hill any credit, but they reference Pepoon and “the base of a limestone ledge near Lemont.” They map reports of M. mutica from five northeastern counties but not with the dot that means they’ve studied the herbarium specimen. Instead, the map has just triangles, which mean “we have not seen a voucher specimen, but that there is a record in the literature.”

The plot thickens with the 2017 publication of the Flora of the Chicago Region by Wilhelm and Rericha. Botanists have rather a sweet and polite way of saying another botanist was wrong. To reject a report of Species A, they write that that report “is being referred to” Species B. In the case of the long-lost M. mutica, Wilhelm and Rericha write:

Specimens called Melica mutica that are from “base of limestone ledge” near Lemont in Cook County (Hill) and “sandy bank” on Altorf [Langham] Island in the Kankakee River (Boewe) are Melica nitens. … All the specimens that we have seen thus labeled are referable to M. nitens. Until such time that we discover authentic material, we have excluded M. mutica from the flora [of the Chicago region].

In other words, Hill and Boewe and everyone who reported Melica mutica from the Chicago region had all messed up. Confusion between these two plants is not surprising. The many floras I’ve checked give very different ways to discriminate between them. Two-flowered melic grass is said to usually have flowers in twos, and tall melic grass usually has flowers in threes. Some other criteria depend on overlapping average measurements and are often accompanied by drawings that seem to contradict features as described in other floras. At Lemont, Hill had just one plant to judge from. Might not the fact that it was at the base of a limestone ledge result in a “depauperate” specimen with reduced features?

In any case, Wilhelm and Rericha are convincing, in that they actually compared the herbarium specimens to our current understanding of the features of these species. The Langham Island specimen and all the others in northeastern Illinois were nitens – tall melic grass – not endangered but, according to Mohlenbrock, then known to survive in Northeastern Illinois at just one site. It’s a rare plant.

Wilhelm and Rericha refer to tall melic grass as “Rare, this species occurs in mesic savannas and prairies.” With a nice round dot they map authentic specimens from Cook, Will, Grundy, and Kankakee Counties. Yes! John Sullivan found the actual, long-lost rare species at Langham. It’s back, baby!

And yes, tall melic grass is just “rare” and not on the Illinois endangered list. But this rare plant was part of the rare community on this extraordinary “island of rare plants.” Its genes and whatever may be unique about them still live!

Long may it wave in beauty-is-in-the-eye-of-the-beholder glory – as Langham Island recovers its wondrous diversity.

Endnotes

Endnot 1. Why Care About A Rare Grass?

(This endnote is adapted from a similar passage in a post on Junegrass.)

We value biodiversity in part because we may need its genes. Grass feeds the world. Such grasses as wheat, rice, corn, oats, rye, sorghum, millet, etc. provide a large part of human food directly or indirectly, and pasture grasses support most domestic animals. Many people look forward to specialized or improved grains (and legumes) for superior health and nutrition values.

As plant diseases evolve, crops are only kept viable by agronomists who can regularly find needed genetic material from wild relatives. We want to keep diversity alive to cure diseases (in humans or in crop plants) and also make various crops more “heart-healthy” or nutritionally superior in other ways. The tropics have great genetic diversity, but we may need genetic alleles that work in the prairie soils, which play so disproportionately valuable a role for the planet. We want to leave the richness of biodiversity heritage for future generations.

How much should we care about “rare” as opposed to “endangered” species? The official endangerment of a whole species is an easy concept to understand, but it misses the major point of conservation, especially for the tallgrass region. In some other places, micro-habitats create micro-species with limited ranges, and many slightly different species grow there. People would say they’re “hot spots” of species diversity. They are important to conservation. But the emerging field of biodiversity science struggles to get across the point that biodiversity conservation has to be pursued at three levels: the gene pool, the species, and the ecosystem. Not just species.

We in the Midwest strive to be stewards of ecosystems and gene pools made up of species with ranges often extending from the Atlantic to the Pacific and even across oceans. A species may not be endangered, and yet important parts of its gene pool may be. Though Melica mutica is endangered and Melica nitens is not, that official status may be less important than the fact that either species (and even some “globally common” species) may have populations in unusual situations that have endangered alleles.

No one understands why Langham Island has so many rare plants. Let’s just admit that there is something special about the place. High, dry, limey, and somewhat isolated, it’s a challenging habitat in an increasingly challenging world. Seeds and pollen have travelled to the island by wind and water for millennia, and yet unusual plants survive. Doing our best to conserve them seems right.

And consider another endangered plant of Langham, the leafy prairie clover. It was long ago found in six Illinois counties. It is now extinct in five of those. Globally, it survives in a few small populations in Illinois, Tennessee, and Alabama. As with grasses, being a legume (bean), it may harbor valuable alleles for nutrition. Also, it’s just obviously special – and part of a special ecosystem. Long gone from Langham Island and believed extinct in this state, one Illinois population was re-discovered in 1974 by Gerould Wilhelm. A handful of others have since been found. With seeds from those, Illinois state botanist John Schwegman attempted to restore leafy prairie clover to Langham in the 1980s. That attempt seems to have failed, so far. Restoring a species sometimes takes a number of tries by a number of approaches. We should continue to try. The formerly absent mallow and corn salad have now been joined by tall melic grass to send a message. This ecologically rich, special island is coming back.

Endnote 2. Yet more thrilling detail about the discovery.

The timeline below gives some hints to how and why amateur botany works.

Cast of Characters

Christos Economou: Volunteer steward at Somme, Plank Road, and Langham

Katie Kucera: On staff in the Plants of Concern program at the Chicago Botanic Garden. Volunteer steward at Somme.

John Sullivan: Volunteer steward at Langham Island.

June 9, 2022, 9:41 AM: Texts indicate that a search for two rare plants was being planned by Christos Economou and Katie Kucera. Their quarry: Calystegia spithamaea and Melica nitens – upright bindweed and tall melic grass. As the stewards have been doing for decades, they were searching for “refugee plants” for possible restoration to restoration areas at Somme, Shaw, and elsewhere.

June 9, 2022 11:08 AM. John Sullivan near Kankakee independently puzzles over a rare grass and submits a photo to iNaturalist for identification. "K3outdoors" suggests it may be Melica nitens.

June 12, 2022, 6:08 PM Test from Katie Kucera reads: “I think John Sullivan (if I have his iNat correct) found Melica nitens on Langham last Thursday!” Economou replies: “Woah!!” Katie mentions that she was actually at Langham with John Sullivan that Thursday but didn’t hear about the find.

June 18, 2022: Christos Economou gathers seeds of Melica nitens at Langham Island, to be broadcast in additional recovering areas of the island. Langham botanist Ryan Sorrells studies the plant and confirms, if there were still any doubt, that it is indeed the rare Melica nitens.

Christos Economou and team collect tall melic grass seeds for restoration.

July 28, 2022: The Langham stewards planning group has an actual sit-down meeting at the Hoppy Pig in Kankakee. Reviewing documents, studying options, and agonizing over details, it slowly dawns on us that the melic grass found on the island may be the rare grass found on the island decades ago. A check on the plant in The Vascular flora of Langham Island by botanist John Schwegman (1991) reveals that he found no melic grasses among the 315 species while studying the island in 1985 and 1986. This rare plant apparently emerged in response to the dedicated brush clearing and burning on Langham which volunteers have done since 2014.

In the end, Wilhelm & Rericha’s careful taxonomic work for the Flora of the Chicago Region convinced us that, yes, the lost has been found. Onward and Upward!

Summer and Fall 2022 and beyond: The revived melic grasses are currently growing in sparce, immature communities on relatively bare ground where brush had recently been cut. They may not continue to grow where John and Christos found them. As the island recovers, all plants will need to contend with an increasingly competitive, conservative turf. Thus, they may need to end up in different places from where they now grow. We gather seeds and disperse them widely throughout the island's appropriate micro-habitats to give plants, especially the rare and conservative ones, opportunities to find sustainable niches in the various degrees of shade, subtypes of soil, aspects, degrees of slope, and plant associates that will be home for them in the long haul.

The Friends of Langham Island continue to work, study, and celebrate. Great job, team!

Acknowledgements

We owe most of the plant location information we use to make conservation decisions to dedicated amateur botanists from E.J.Hill down to John Sullivan, Christos Economou, and Ryan Sorrells. Bless them.

Conservation also owes most of the coordination and verification of plant data to professional botanists including Katie Kucera, Laura Rericha, Jerry Wilhelm, and (at the aspiring and student level) Ryan Sorrells. Bless them as well.

Thanks for info, edits, and proofing of this post to John Sullivan, Eriko Kojima, Mark Kluge, Matt Evans, and Christos Economou.

Melica nitens is a beautiful native grass that seems to love open woodland areas. The discovery at Langham is a wonderful example of the response to removing invasive species and introducing fire.

ReplyDeleteHere is an account of the discovery of Melica at Cranberry Slough NP in July 1999. It was the second of two unforgettable days of my life. I was pacing the perimeter of Buttonbush Slough and I stopped for a break at Little Buttonbush Slough. There I saw a juvenile sandhill that was as tall as its parents (also present) but still covered in yellow down feathers. He looked exactly like 'Big Bird' from Sesame St. I was really excited. I did not have a camera with me. So the following day I took my camera to Cranberry in the slim hope of capturing an image of the juvenile sandhill. (On reflection this action reflects the thrill I had rather than clear thinking. I have never seen a large juvenile sandhill before or since, and I am not an experienced photographer). While wandering around I found a nice size (3m x 2m) patch of a beautiful grass I had never seen before. I instinctively knew it was native. When I keyed it out, I came to Melica mutica, a really exciting find. Later John Schwegman let me know it must be Melica nitens (which grows to 1.3m and not M. mutica which only gets to 70cm high). I do not collect specimens of native species as I am trying to enhance the species, not serve curators.

ReplyDeleteThe place Melica was found at Cranberry had been burned 4 times between 1986 and 1999. I grew Melica nitens at UIC. The seeds are very hard and smooth. The shape reminds me of a torpedo. I have spread seed at Cranberry, but Melica also popped up in unseeded places. The abundance at original location has declined but there are now 4 or so locations at Cranberry with many individuals. All the populations I know about are within parts of Cranberry that have been burned many times.

I hope the efforts to increase the population at Langham are successful. Increasing available light at waist height will help Melica (and others). Fire seems to be important at Cranberry, but I can't directly cite concrete, recorded experiences. Melica nitens grows fine in a garden where more seed can be produced than can be gathered from nature.

Dennis Nyberg