In 2017, many of us noticed that a major invasive, garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), seemed to be drastically declining or gone - as discussed in a 2017 post.

Here's an update for 2022. In some areas garlic mustard is still gone. In others this bad plant still rages.

It seems unlikely that a disease was the principal control, though it would be good to read any studies or observations that suggested otherwise.

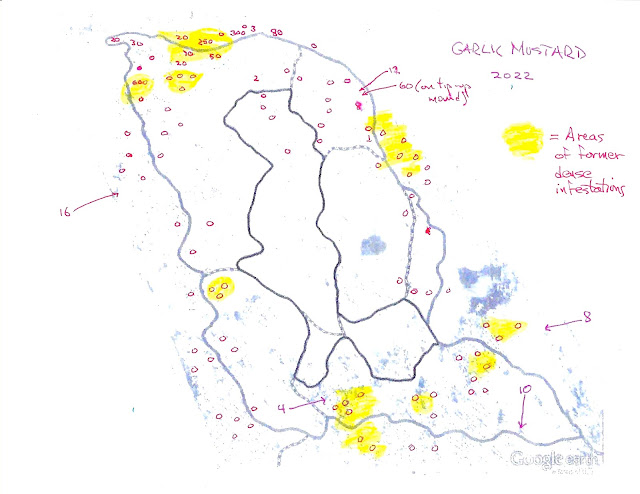

In the map below, a "0" indicates a place where garlic mustard is now gone from an area of Somme Prairie Grove (SPG) where for years there was masses of it - thigh-high and solid. There were acres of such ecosystem misery. At other nearby sites, this invasive seems still to be a major problem.

We compiled the map below while doing other work. (If infestations were minor, we pulled when we mapped them.) The numbers show how many garlic mustard plants were found at the points indicated. A "0" indicates a point where we remember finding garlic mustard in the past but where we found none in 2022. We found only 22 plants, most of them very small, in the southern half of the site, where there had been thousands every year for many years. There are still more than 1,000 plants along the northern edge of the site.

Over the years, we have carefully pulled every garlic mustard we could find in the better-quality areas, as we are doing this year. But it seems impossible that we find them all, especially the very little ones that still can make a few dozen nasty seeds. Thus it seems that, if we pull the big ones from higher quality areas, we can largely eliminate it there.

To emphasize this point, the map below shows the same 2022 data but with heavy infestations from previous years shown in yellow. Note that, in some areas with former heavy infestations, we could fine no garlic mustard plants this year.

The yellow areas are just from memory. (See Endnote 1 for comments on the science.)Some of the areas that have dense concentrations now also had it dense for years, so it seems unlikely that disease build-up is what's conquering it.

Tentatively, there are two likely explanations for this positive report:

1. We switched from a strategy of "get as many people to pull as many plants as possible" to a strategy of "herding invasives." We focused most of our attention on areas where there is the least. Thus we remove the outliers and drive the edges back until we can pull the last ones.

(In the past we often had large numbers of people pulling, and our group trampled many and left many broken off stems to re-sprout and produce a few seeds each. It doesn't take many surviving plants to maintain a dense population. These days, more expert weed-pullers follow up on the big groups.)

2. Perhaps equally important, we have planted full-spectrum seed mixes: common plants and conservatives ... spring, summer, and fall species. All the large garlic mustard populations are now in areas where the restoration is young and new. It seems likely that in the more mature areas, after we pulled all the big ones, competition eliminated the others.

People with additional garlic mustard observations are invited to comment below or send comments to info@sommepreserve.org or here.

Endnotes

Endnote 1. On the science.

The rough maps above are our contributions to science on this. The numbers are hard data, in a sense. For the small populations, they are not samples or estimates, they are numbers of counted plants. On the other hand, many small plants were probably missed. In the case of the large populations, we counted some sample areas and then multiplied by the number of such areas in the patch. Those numbers are thus estimates.

In the past, thinking that good science was needed and that good science required the scientific method and statistical significance, we on occasion took data in some of those dense mustard concentrations. We imagined that we'd later go back and resample. That's now obviously not remotely worth the effort, unless perhaps by someone working toward a degree or for an academic publication. For us to do the work of re-sampling just to say that an area once had 100% mustard cover and now has 0% seems like a waste. We are learning what we want at SPG without the numbers.

It seems likely that garlic mustard is as widespread a problem as it is because our woodlands generally are degrading, losing diversity, because of lack of fire. The garlic mustard could be seen as more of a symptom than the problem.

But more data from more varied sites and management regimes is needed to draw more general conclusions.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Eriko Kojima for proofing and edits.

Strong, healthy, dense native communities indeed seem to compete successfully with many invasive species. The right kind of fire management may be critical factor. There appears to be no super solution to this set of issues and never may be.

ReplyDeleteGarlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is a species that has a very prolonged period (April through July - and longer) during which it will emerge, bolt, and develop seeds. To prevent any seeds from developing and reinforcing a seed bank the plants must be searched for and removed at least every two weeks! That means that an area must be at least scanned and “plants pulled” about 8 times during a growing season; 2 or 3 concentrated workdays will not be sufficient to get rid of the stuff. “Constant Vigilance!” as Mad-Eye Moody would say. Because only some seeds in a seed bank germinate from one year to the next, that vigilance must continue for years until the seed bank is depleted.

ReplyDeleteLarge numbers of “pulled” plants should not be piled together, because their moisture will allow some to continue to mature with subsequent development of viable seeds. If the plants can not be removed from the site, then create a dedicated weed disposal area that can be herbicided as things do germinate. Adequate disposal of weeds is essential for their eradication.

A late spring prescribed burn will kill emerging seedlings and weaken more developed plants. A strictly anecdotal observation is that a prolonged snow cover (December through March) seems to have set back development of garlic mustard twice in the last two decades.

Thanks to Kirk for good observations. One approach that has worked for us in the case of large populations has been to gather bushels of the plants and make piles, sometimes (in the past) four or five feet high, and leave them for two years. In the first spring, a "chia pet" of cotyledons would emerge and mostly kill each other off. In spring of the second year, before they bloom, we would then pull the dozen or so that survived, and that would be the end of them (although we typically put these piles by a trail where we would pass by and check for years, just in case).

DeleteI agree with the "chia pet" phenomenon; at Deer Grove we have had much luck with composting in the same spot for many years, with little or no spreading beyond the chia pet stage. I can't explain it beyond the fact that it works, and we have at least three dedicated composting sites that we have used for many years.

ReplyDeleteI like the "herding invasives" phrase, which can be applied to many invasives with mono patches and then outliers. But, there are different situations. At one of my sites the GM seems to be growing vigorously in among the spring wildflowers. So rather than weed the outliers (in lower quality areas) before working up to the more rich areas with rapidly oncoming GM plants, I am planning on going after the species-rich area first to rid it of the GM plants before they spew their seed all over.

Great use of mapping to track an invasive weed!

In our park in Madison, WI we have found a flea beetle feeding on both first year seedlings and second year garlic mustard plants. It has been identified as a species of (Phyllotreta sp). It has some similarity to the European species Phyllotreta ochripes which also feeds on garlic mustard. A similar beetle was reported from DuPage County IL in 2016. Check for beetle damage.

ReplyDeleteI think an over abundance of deer has to be a factor in the overall health of garlic mustard. They spread the seed, eat competition and prepare the ground for seeds.

ReplyDelete