Among farms and in surrounding semi-wild lands, Frank Baker

studied the mollusks. But, as chief curator of the Chicago

Academy of Sciences, he sought to “take an ecological approach.” He tried

something new as a scientist – recording not just the mollusks, but also their

associated plants, insects, reptiles, amphibians, and birds. His principal colleague seems to have been Frank

Woodruff, who did the birds and took most of the habitat photos.

Woodruff had published “Birds of the Chicago Area” one

year earlier. In it he had written:

“As our territory becomes more

thickly populated each year, the struggle for existence among our wild birds to

remain and breed in their old haunts is really pitiful.”

Baker's and Woodruff’s attempt at an "ecological approach" stands today as an unrivaled

ecological snapshot of Northern Illinois woodlands and wetlands. Back then, sadly,

it didn’t seem to have made much of an impact. It was too far ahead of its

time. “Ecology” was a newly coined word for a discipline in its infancy. Explaining why

he was wrestling with questions of holistic habitat, Baker expressed the

belief that his paper “may be one of the first attempts to apply the ecological

method” and cited Henry Chandler Cowles' 1901 book. Yet, Cowles book was limited

to plants' relationships with each other and with soils and landforms. Baker

reached higher.

During his life Baker published nearly 400 books and papers,

mostly with titles like “The Lymnaeidae of North and Middle America, recent and

fossil.” Sadly, neither he (nor anyone else?) soon wrestled again with so ambitious an approach

to ecosystem monitoring. But Baker’s team left us a treasure.

Baker’s paper summarized the biota at 35 “stations.” (The

map recorded 36, but that last station, the west fork of the North Branch of

the Chicago River just south of the village of Northbrook was dismissed with

this macabre note: “It is used for sewage purposes, and is, therefore, a

difficult stream to study.” (It may be worth noting that photos show scientist

Baker wearing a white shirt and tie in the field.)

|

| Baker's map shows Dundee Road with the Great Skokie Marsh on both sides. Today, to the north, the marsh has been replaced by Chicago Botanic Garden. To the south is "Skokie Lagoons." |

Station 2 on Baker’s map was in marsh, where Woodruff’s list of nesting birds is an eye-opener (see

below).

To knowledgeable birders today, the above list is nearly beyond belief. Many of these species no longer nest in the Chicago

region at all. Today four of them are on the Illinois Endangered list: Northern

Harrier, American Bittern, Florida Gallinule, and King Rail.

|

| Harriers once hunted for voles over every tallgrass marsh and prairie. Today they rarely find enough habitat to nest anywhere in Illinois. Photo by Jerry Goldner. |

|

| In 1907 (according to Woodruff) “a common summer resident” - the Gallinule today is a rare treat for photographer Lisa Culp Musgrave, who found this one. |

|

| The precious and beautiful little Leconte’s Sparrow no longer nests any closer to Chicago than northern Wisconsin. Photo by Jaculin Bowman |

And did Woodruff really find all those nest sites? It seems

so, as he points out that he did not find nest sites for two of the species.

Perhaps in some cases he saw parents carrying food and acting agitated, strong

indications that their nest with chicks is nearby.

Many species back then showed an

abundance that seems mythic today. For example, reporting on the prairie

chicken, Woodruff writes:

“In many places the farmers are in

the habit of collecting their eggs by the pailful to use for culinary purposes.

Such a drain as this, with the annual slaughter by sportsmen, and the

restriction of their breeding grounds by cultivation, is gradually lessening

their numbers except in the remote prairie districts.”

Gathering eggs of wild birds by the pailful? Woodruff’s book

lists American bittern, King Rail, Yellow Rail, and Florida Gallinule as “common

summer residents.” Maybe Woodruff was very good at finding nests. Maybe “common” then was on a whole different scale from what that word means

now.

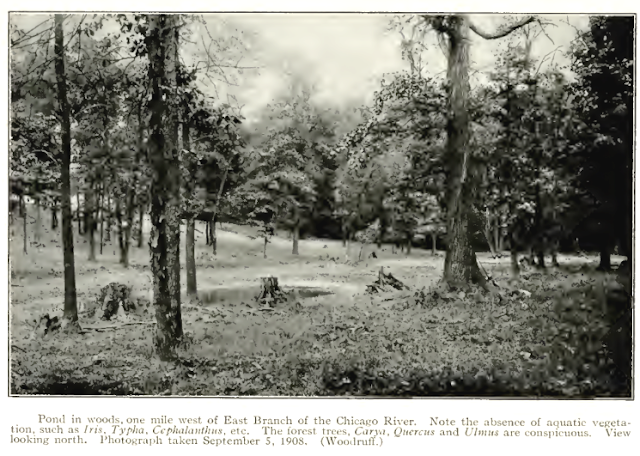

On September 5, 1908, Frank Woodruff snapped this photo of “Stations

3 to 5” -

Earlier that year, at this station, Woodruff had recorded

red-headed woodpecker and nesting shrubland birds including yellow warbler,

indigo bunting, and brown thrasher. Surprisingly, to me at least, he also found

nesting wood thrush, a bird more typical of larger, deeper woodlands. Perhaps,

when there were so many birds, they overflowed into more types of habitats than

they do today.

In fact, in many of the areas Woodruff surveyed, the birds

he recorded would not today be likely found nesting near each

other. Is it possible that a quality habitat has more niches for (and diversity

of) birds? Bird conservationists today recognize certain areas as especially

important. Often we’re not sure just why one area is so much better. We just

know that’s where the birds are.

Bless their hearts, Baker and Woodruff really tried to study

habitats and give us both photographs and detailed drawings. For example,

Station 7. The photo below shows a “large marshy pond” in an unprepossessing

corner of a farm, with “forest” in the background.

The pond is thick with tall dense vegetation. The photo gives me a lot of information, but plant species detail is limited.

So Baker provides a remarkable sketch of the vegetation of Station 7 in six concentric “zones.” (See below.)

In the middle zone is cat-tail (Typha) and a few willows

(Salix.) The next zone out is blue-flag iris mixed with arrowhead (Sagittaria).

Then comes a ring of shrubs: hawthorn (Crataegus), crabapple (Pyrus), and

viburnum. Last comes the forest, surrounding the pond, predominantly oaks

(Quercus) joined by hickory (Carya), hop hornbeam (Ostrya), and aspen

(Populus).

Baker identifies additional plant species, many insects, a

crayfish, and thirteen species of mollusks (all snails?) in the various zones. Who

today knows the snails? Are any of these species of conservation concern? Do

they still crawl in our forest preserves?

Yet we have to admit the same problem Baker and Woodruff

had. How do we best monitor, understand and manage all that complexity of

nature? Though dedicated Somme sub-groups are paying special attention to rare

plants, shrubs, trees, sedges, birds, dragonflies, and butterflies – no one

does the snails. Illinois conservationists initially focused on plants. As we improved our understandings of bird and butterfly needs, conservation actions changed for

the better.

Woodruff photographs some stations without recording the

birds. None there? Too much to do? Perhaps Woodruff helped Baker a bit

and then ran off to the big marsh to find more birds’ nests – or to the rich Station 28 (see: http://woodsandprairie.blogspot.com/2017/12/the-unexpected-discovery-of-somme-woods.html) – the only area where he claims to have identified the “summer resident

birds.” A few people can’t give maximum focus to all biota at every site.

Plant identification in Baker’s study is credited to Henry

Chandler Cowles and Miss Carrie A Reynolds of Lakeview High School. Various others are

thanked for help identifying beetles found with snails under dead bark, aquatic

insects, and crayfishes. No one gets credit for reptiles and amphibians,

sadly, and attention to them was minimal. No one did the spiders, or bees, or

mammals.

Surprisingly, for a mollusk study titled “Ecology of the

Skokie Marsh Area,” only one station was in the actual marsh. Baker instead

spent most of his time on woodland ponds and streams. By far the richest of

these (at least so far as plants, birds, and mollusks were concerned) was Station

28 (see link above). An interesting comparison with the rich woodland photo there can be made with the sorry state of Station 32

(below).

Station 32 had few birds, few mollusks, and few

herbaceous plants or shrubs. Baker points out the lack of vegetation in the pond itself,

but equally striking is the higher ground, which seems to have little but dead

leaves. What happened here? Perhaps it was exploited to death. Grazing by cows?

Sheep? Pigs? Stumps show that the larger trees were cut. With more light, you’d

think there’d be more vegetation. But all those hungry mouths kept it eaten

down?

This post ends with Station 34, which, of all amazements, turned out to be right behind my house, in Somme Woods South.

At Station 34, Baker found six mollusk and three beetle species. Woodruff found nesting bobolinks and meadowlarks. Certainly today, such a little scrap of grassland would not be honored with them. In the scattered trees he found nesting field sparrows and brown thrashers. Station 34 today is a forest preserve – without a square foot of grassland. I remember a little patch still there, decades ago. Today you can easily identify the former grassland; it’s dense buckthorn – with no old oaks. No birds of conservation significance nest in this preserve. I haven’t checked for snails, but …

We have lost a lot of nature – and saved a lot – since the days of

Baker and Woodruff. A great many dedicated conservationists do as much as we can – given the resources,

people power, and political will. Decades ago, a globally significant

professional and volunteer constituency rose up, chipped in, and inspired

vastly increased resources for local conservation. (See, for example: http://woodsandprairie.blogspot.com/2015/03/stewards-of-nature-early-years-of.html)

Our predecessors inspire us still. If you're not yet involved, join in?

References

Baker, Frank Collins, “The Ecology of the Skokie Marsh Area,

with Special Reference to the Mollusca.” Bulletin of the Illinois State

Laboratory of Natural History, Urbana, Illinois, U.S.A. Vo. VIII. 1910

On line at: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle /2142/55226/Bulletin8%284%29.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

Cowles, H. C. 1901.

The Plant Societies of Chicago and Vicinity. The Bulletin of the Geographic

Society of Chicago, No. 2.

Woodruff, Frank. Birds of the Chicago Area. 1907.

On line at:Bird bonanza https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=75waAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA18

Bonus photo:

An American bittern in a tree is an uncomfortable bittern. They stand - three feet tall - in grassy marshes with their bills pointing straight up - invisible. American bitterns make one of the most spectacular mating calls of any bird. When we restore marshes big enough and good enough for American bitterns, we’ll have really done something. Photo by Jerry Goldner.

Thanks for sharing the photos from 1908... I'd love to learn whuch species of snail are conservative to various wetlands. I've observed some species eating cattails in nearby marshland - maybe these mollusks kept cattails in balance when life was much more abundant in our wetlands!

ReplyDeleteThe picture in the below link is of a retention pond in Schaumburg’s Henry Terada Park that is being restored. The city’s conservation staff had to work for a long time to convince the city to do this project. Some of the residence did not want the country club look of the park altered. Although, I think they all mostly like it now.

ReplyDeletehttps://plus.google.com/u/0/photos/photo/107874019080399894118/6508325759921220722?authkey=CJ7KlLyVvseZQQ

The list of birds I have seen at this park is not as extensive as Woodruff’s. However, I have seen song sparrows, red-winged blackbirds, king bird, Virginia rail, cormorant, mallard duck, and of course Canada goose in addition to egrets and herons shown in the photo. In late summer when the water level drops there are shore birds in the mud flats that I have not yet added to my list, but I believe one species is some type of plover. I think I also remember seeing marsh wren. I spend my time improving the plantings and therefore have not put enough effort into identifying all the birds that use it.

Very detailed analysis are available for calculating the economic value of street trees. They have the economics down to the dollars and cents saved in home heating/cooling, savings from reduced storm water infrastructure, value of the air pollution that is absorbed, improved real estate values, and even the reduction in medical costs from the reduced stress levels of those who live in neighborhoods with trees. It would seem worthwhile to similarly calculate the economic benefits provided by wetlands and prairies too.

Congratulations to Schaumburg for good work. Every park (and every subdivision retention pond) should include some natural habitat. Good for kids, wildlife, and the rest of the universe. Habitat for Virginia rails and song sparrows is also habitat for frogs, butterflies, and us. Hey, People of the Suburbs! Let's do more of this! And let's celebrate it and teach it to one and all!

DeleteI grew up in Schaumburg and the value of their natural areas such as they are is incalculable. Great wildlife around the Gray Farm Park area by what is today Blackwell school. by the little board walk used to watch yellow headed blackbirds, recently there was a rail there laughing it up not six feet away, but invisible because of the dense cattails. yh blackbirds like open marshes with about 1/2 cattail emergent and half open water, feeding their chicks abundantly on newly emerged dragonflies.

DeleteNature is always changing, but human economic activity usually leads to abundance declines of native species. The decline in bird abundance around Somme might be the result of a large decline in insect abundance due to expanded number of residences and use of chemicals for insect control since WWII. In general, bird species composition and abundance is poor for measuring local change, because birds move around much more than other species. Some part of the decline in bird abundance is probably due to increased economic exploitation of the rain forests in South America.

ReplyDelete